A Visit to Dharavi, one of Asia’s Biggest Slums

”To a devout low-caste Hindu, the recycling process might offer solace, for through its gyrations rejected goods come back in new and valuable forms. At the first turn of the wheel is Ravi, a scavenger waiting outside a garbage wholesaler to unload his day’s labour – a sack of paper and plastic plucked from Dharavi’s rancid alleys. Ravi is balding, has rotten teeth and reckons he is 35. He says he arrived in Mumbai from Nagpur, Maharashtra, about 25 years ago, after fleeing a cruel stepmother. The journey took him a bit over three years, most of which he spent in prison; he was arrested aboard a train leaving Nagpur for travelling without a ticket. Since he got to Mumbai, he has spent every night on a nearby railway platform, and his days scavenging. Earning around 20 rupees (50 cents) per kilo of plastic litter, Ravi makes between 50 and 100 rupees a day—of which he aims to send 1,200 rupees a month to his younger sister in Nagpur. He has not been home, or seen her, since running away as a child. He explains this act of almost incredible selflessness thus: “I have no attachment to anyone except my sister.”[1]

A ten-year old boy runs away from home, ends up in a big city, all by himself, sleeps on a railway platform, survives as a refuse scavenger and sends money to a sister whom he hasn’t seen in twenty-five years. What’s left when we are on our own out there, what keeps us going, what is worth living for?

In my twenties, a French book touched me profoundly: Dominique Lapierre’s “Cité de la Joie”, an ode to the unknown heroes of a slum in Kolkata. Many years later, I read “Shantaram”, Gregory David Roberts’ novel on the life of an escaped convict in Bombay’s tumultuous underworld and slums. When my husband and I decided to travel to Southern India at the end of last year, I knew I wanted to visit a slum.

Of course, I asked myself questions. Why do I want to see a slum? Do I want to see poverty because of the thrill? In order to take good pictures? Is it ethical? Isn’t it just voyeurism? Am I one of the many travellers in search of sensationalism, of the ego trip that gives you that extra kick, the ultimate experience designed to invite admiration?

In my case, it was innate curiosity for everything human, all forms of human existence, and the wish to see for myself what I had read: India’s slums are different from our stereotypical perception of despairing places inhabited by hopeless, criminal people. At the same time, I felt ashamed for wanting to see a slum and didn’t tell anyone about it, for fear of being accused of sensationalism – or recklessness. Isn’t it dangerous, wouldn’t I risk catching dreadful diseases?

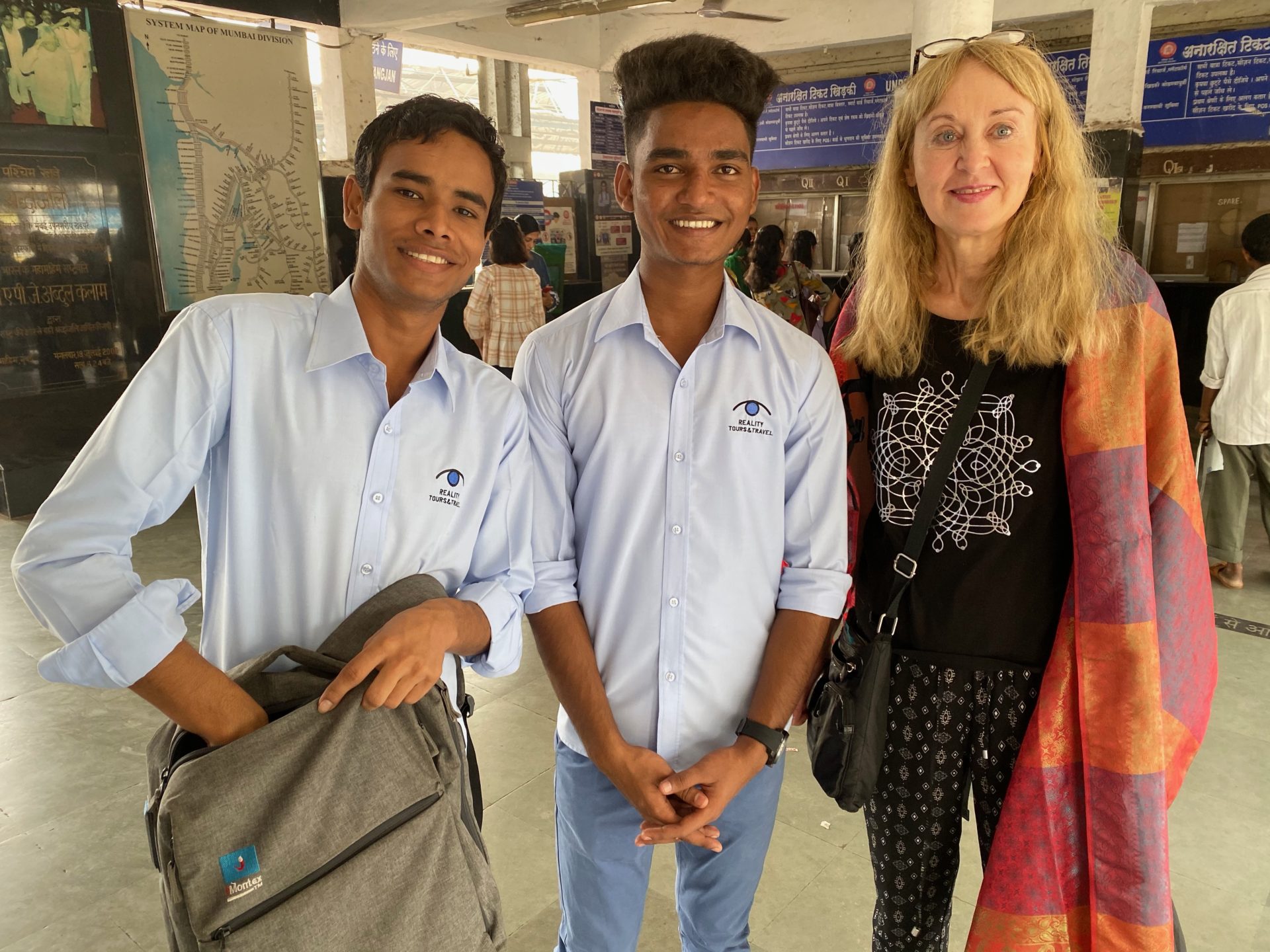

Slum tourism is not a new phenomenon. It already existed in the 19th century. In the 1860s, “Slumming“ was added to the Oxford English Dictionary, meaning “to go into, or frequent slums for discreditable purposes; to saunter about, with a suspicion, perhaps, of immoral pursuits.”[2] Since then, much has changed. No doubt, there are still people who wander about slums with immoral intentions, but today’s organized slum tours are designed for different purposes. The Dharavi-based agency Reality Tours and Travel[3] says it wants to challenge our common perception and “use tourism to change lives”. “Ethical and educational” tours shall give visitors a “glimpse into everyday life for many Mumbaikars”. Most guides come from the slum and 80% of the profits go back into the community. I found this convincing and booked a tour.

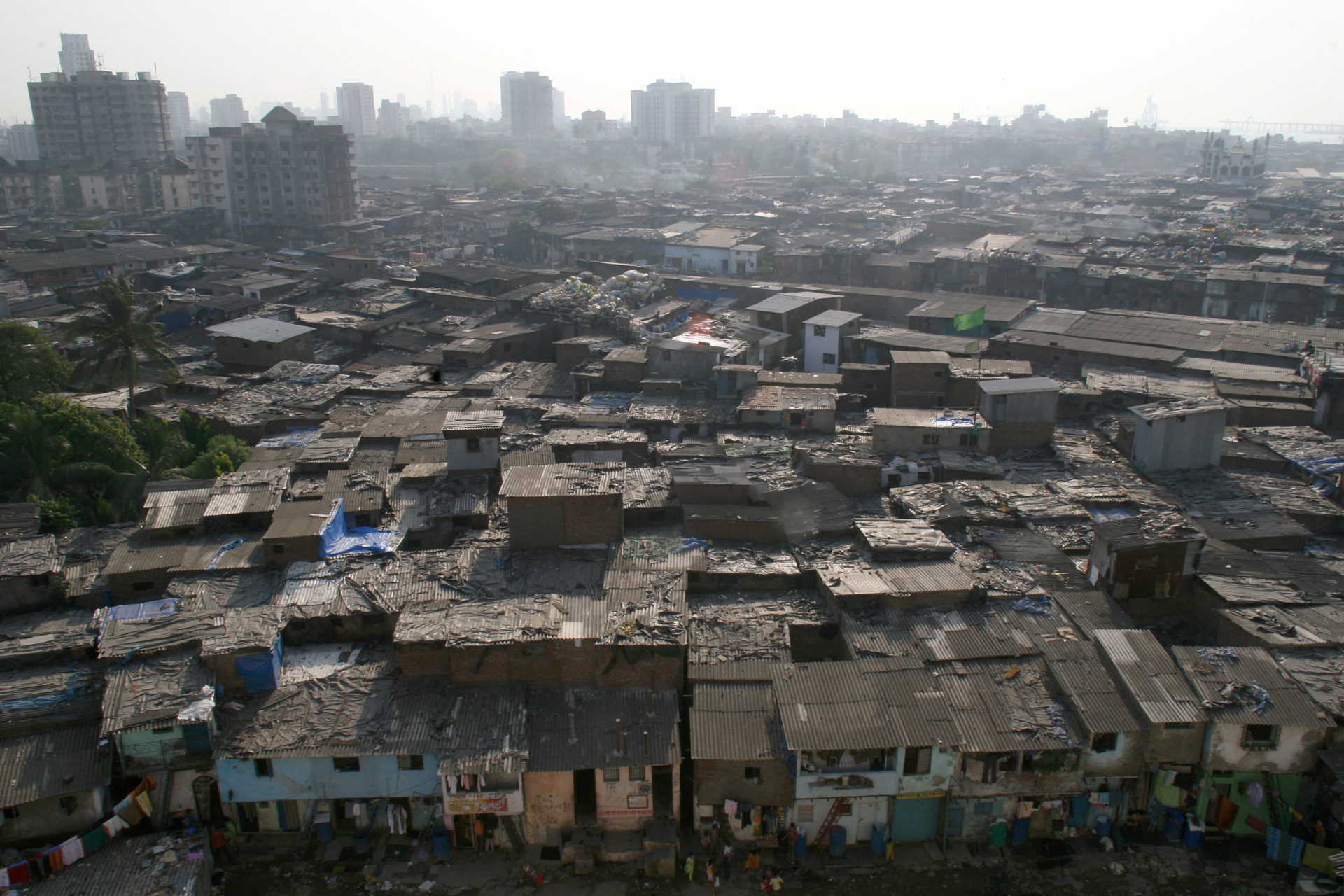

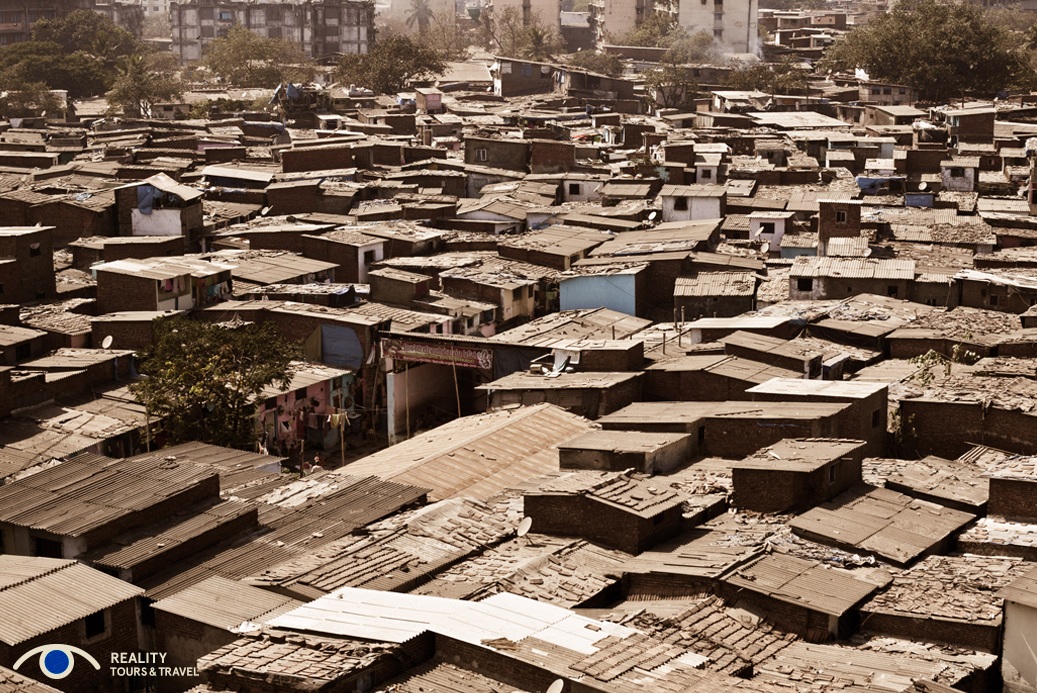

Dharavi is a triangle of land located between Mumbai’s two main suburban railway lines and one of the world’s largest slums. One million people live on a surface area of 2.1 km2, barely two-thirds the size of Central Park in Manhattan, which makes it one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

With decades of urban growth under the British Raj, Mumbai (then Bombay) developed industries that attracted rural migrants looking for jobs. Many settled in Dharavi. They worked with leather, a profession typically reserved for low Hindu castes and Muslims, pottery, fabrics and other kinds of crafts, and in a multitude of small-scale factories. The living quarters and workshops grew haphazardly, without sanitation, drains, roads or safe drinking water. In 1887, Badi Masjid, Dharavi’s first mosque, opened its doors, and in 1913, a Hindu temple was built. When India became independent in 1947, Dharavi was India’s largest slum. Meanwhile, Mumbai continued to grow, and Dharavi found itself surrounded by a metropolis. There have been many plans to redevelop the slum but so far, none was successful.

Our tour starts on our second day in Mumbai, at Mahim railway station. We are expecting a guide with a pale blue shirt with the agency’s logo on it. I am anxious: what if, in the face of extreme poverty, I turn out to be faint hearted? What if I faint because of the smell? When we get off the rikshaw, a boy approaches us begging for money. I give him some food. He points towards a woman lying on a blanket on the sidewalk and taps his forehead. “My mother”, he laughs. “She is crazy!” Oh my God, I think, I am not sure if I can take this. “This is only the beginning,“ my husband observes.

At the station, two young men with the agency logo on their shirts are waiting for us. One has a cake hairstyle, currently popular in India, and his companion is Tavrej, our guide, a shy, friendly young man from the slum. We are a small group of six people: We, a Czech-Austrian couple, two Italians and two Australians.

Tavrej gives us the basic instructions for the tour, such as the ban on photography. I love taking pictures, especially portraits, and on that tour we could have taken great pictures. I must admit that the ban saddened me a bit. But I understand why the measure was taken: a slum tour should not be merely a photographic excursion, with the slum-dwellers reduced to great photo opportunities. Visitors should be interested in what they see with their own eyes – and not mainly in what the lens can zoom in on. Mahim footbridge, the entrance point to Dharavi, is my last opportunity to take a picture.

“Have you seen the Oscar-winning movie Slumdog Millionaire?“ Tavrej asks. We have. “Did you like it?“ Well, yes, we did. “What about you?“ I ask in return. “The people in the slum don’t like the title“, Tavrej replies. “Why did they call it Slumdog and not Slumboy? No one wants to be called a dog.” He is right, I have never thought about it that way.

During the next three hours we follow Tavrej through a maze of streets, turning into dark, ever-narrowing passages, stumbling over bumps and edges on slippery footpaths, overtaken by shouting children, past lanes of small houses and sheds, catching a glimpse of confined but neat space, of an old woman lying on a couch, of a girl washing her hair in a bucket, past piles of scrap and material of all sorts: plastic, metal, discarded suitcases, computer parts, car batteries and cardboard boxes, entering steaming workshops with bustling activity, taken aback by the impenetrable eyes of determined, hard-working people. The air is humid and sticky, and I am wondering what Dharavi might be in the monsoon period: an urban rain forest, covered by a sky of corrugated sheet metal.

Dharavi is much more than a slum: it is a city within the city, a parallel economy, a self-created economic zone for the poor. Labourers from the countryside come for part of the year to work from morning till night for their employer who provides them with affordable sleeping accommodation above the workshop: six, eight men packed into a single, tiny room. When the monsoon comes, they take their savings and return to their families.

Many of the 15,000 single-room factories focus on the recycling of waste. Dharavi recycles 80% of Mumbai’s solid waste and its annual economic output is estimated to be more than 1 billion USD. The waste is first sorted and separated by recyclables and non-recyclables; plastic is then further sorted by colour and quality. Crushing machines made of scrap waste metals crush the plastic waste into tiny parts which are cleaned and sold to melting facilities. For health and safety reasons, melting machines were banned from Dharavi and the plastic is now sold to industries outside the slum.

Two more traditional industries are typical for Dharavi: Leather and pottery. Dharavi’s leather industry is one of the biggest in the world, providing goods not only to boutiques in Mumbai, but also to international luxury brands like Zara and Giorgio Armani. You won’t find the label “Made in Dharavi“ on these goods, because the brands pay for it to be removed. Thus, it is not unlikely that your fine leather belt or the elegant briefcase you bought as a Christmas gift for your wife were made in the slum of Dharavi.

While leather is a traditional craft of the Muslim community, pottery is a Hindu specialty. Clay is worked by hands and feet into portions that are shaped into pots on the wheel. The pots are baked in kilns and once they are cooled, they are ready to be decorated.

Reality Tours and Travels finances Reality Gives, http://realitygives.org/ an NGO that runs and supports health care, educational and sports projects in Dharavi, such as a football programme for girls, a cricket academy for boys, and English classes for children and adults. “When we asked the people what they needed most”, Tavrej told us, “they said they needed English classes.” Good knowledge of English is a ticket out of the slum, to access better-paying jobs. In Indian private schools, English is the language of instruction and the education provided is of good quality. But poor people cannot afford to send their children to private schools where they would get a real chance of leaving the cycle of poverty their parents and grandparents were trapped in.

We make a stop at the community centre where the English classes provided by Reality Gives take place. A steep stairway leads to a small classroom where several students are waiting, among them a man in his forties or fifties. Taking hold of the opportunity to practice, we engage in a conversation. “Where do you come from?” (I always hesitate between Austria and the Czech Republic, taking turns in naming them). “What is your profession?” “Are you married?” “How many children do you have?” Their enthusiasm is contagious. “What do you want to be?” I ask the girls in return. “A bank manager!” “An engineer!” “A maker of animated films!” are their excited replies. We make a selfie – this is an exception – and I wish them every possible success. When we say goodbye and I am going down the stairs, I realize I haven’t asked the man what he does for a living, whether he still has some dreams in his life. He surely has! Would he otherwise be attending these classes?

These classes are a drop in the ocean, but they are important. Education is hope in Dharavi. There have been many plans to raze or redevelop the slum into a “normal” neighbourhood. But every layer reveals something more complicated, and the question is what would be gained and whether it is a good idea to destroy what has indeed grown uncontrollably, but organically. It was planned to transform Dharavi into a modern township, with high-rise buildings where each family would get an apartment. But the slum-dwellers do not want to move into apartment blocks because they can’t add another floor. If they get 20, 30 or 40 m2, it’s just that, nothing more. In the slum, a family can build an extension if needed, on top of their box-shaped house. They can have their workshops and small factories at home. Destroying these structures would probably push people out into other, worse slums.

We have reached the end of our tour and I am overwhelmed and exhausted, but not faint hearted nor have I fainted or caught a dreadful disease. I will never forget what I saw, it is engraved in my memory. Somewhere I read that the name of Dharavi means “Holding the Sun God” in Sanskrit. I don’t know if this is true. Dharavi is certainly not paradise and I probably haven’t seen its most miserable parts. But its residents do not speak of being miserable. They speak of trying to get ahead, picking every chance they get. May strength and courage be theirs.

***

[1] „A Soul-Searching Business“, in: The Economist Christmas Specials, 19th December 2007.

[2] See also “Inside the Controversial World of Slum Tourism” , National Geographic, April 25, 2018

[3] https://realitytoursandtravel.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dharavi