A month ago I visited Sarajevo – one of those evocative places I have wanted to see for a long time. What comes to my mind when I think of Sarajevo? The Balkans, cultural diversity, East meets West, the Siege and … resilience, survival and the fragility of coexistence. Clichés? Not at all, this is what I found.

My husband says conflicts fascinate me. Maybe he’s right: I want to know what happened, why and how it happened. This is why I booked a so-called ‘War Tour’, half a day with a Bosnian war veteran.

„War Tour“ sounds sensationalist, pretentious, flashy. It wasn’t any of that. It was intense and profound. Adnan, my guide, took me and the second participant of the tour, a young Pole, to several places that played a crucial role in the Siege. He explained why they were important and answered all our questions.

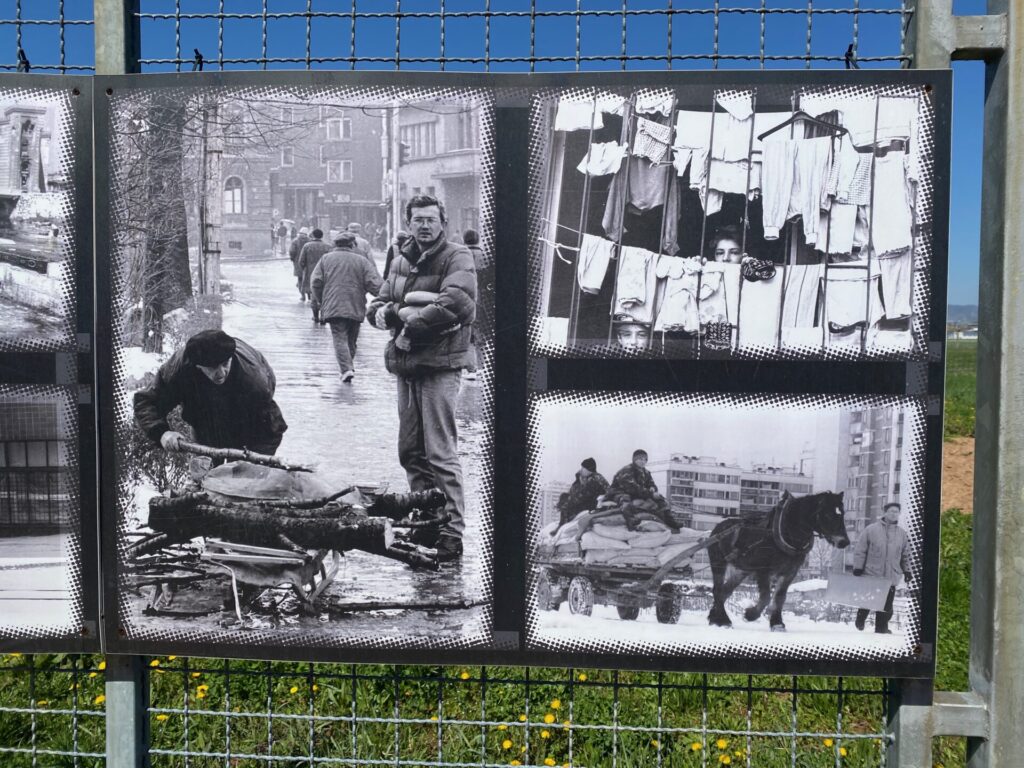

When the war broke out in 1992, Adnan was nineteen. Together with his father, he joined the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. I was naïve, he says, but of course I wanted to defend my city. He had no idea how much hardship and suffering awaited him in the three years and nine months that followed, the longest siege of a capital city in modern warfare.

After the war, he suffered from PTSD syndrome. Today, he is a peace activist and tries to bring together combatants from opposite sides to encourage conversations about shared traumas and the importance of empathy. Veterans, once seen as symbols of conflict, can become agents of peace by acknowledging the pain of all victims. Adnan has Serbian friends but not all Bosniaks have. The Yougoslav war seems to be a thing of the past, but the wounds run deep and the dangers of nationalism have not been banished.

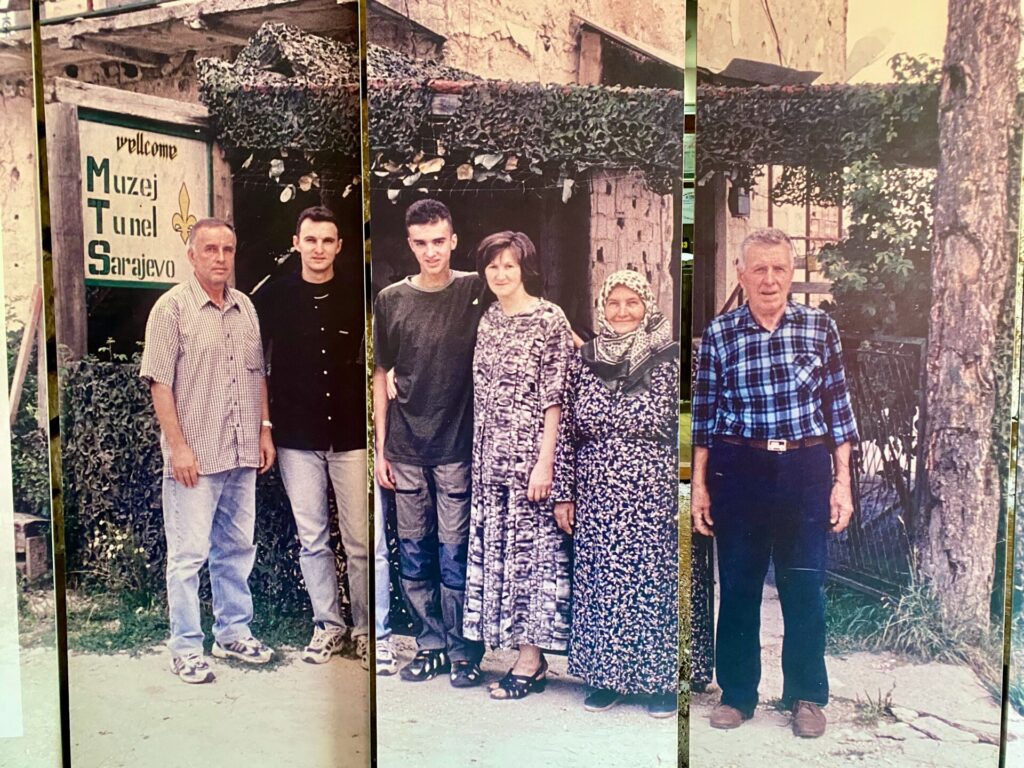

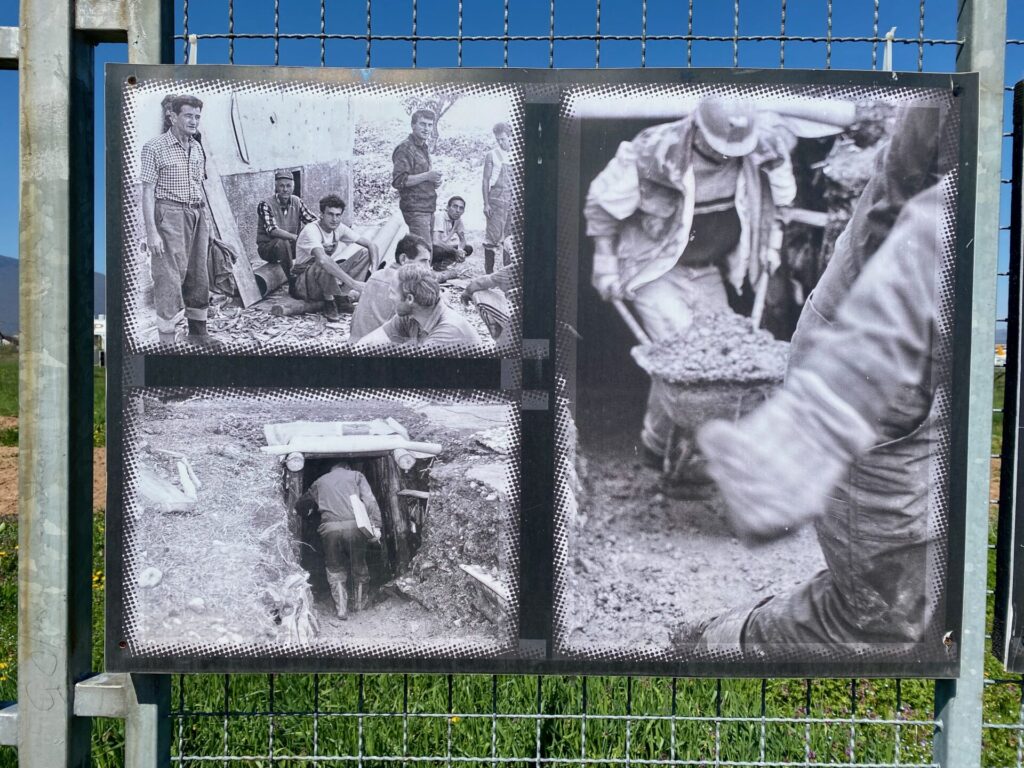

Our first stop was the Tunnel of Hope – Tunel spasa, which was dug by hand under the house of the Kolar family to provide a lifeline for the people trapped in the besieged city. Food, humanitarian aid, weapons, and people were transported in and out. It linked the neighbourhood of Dobrinja (inside the city) with Butmir, an area controlled by the Bosnian Army and near the Sarajevo Airport, which was under UN control.

The tunnel is about 800 meters long and was built under extremely dangerous conditions, with workers risking their lives due to shelling and lack of materials. Ventilation was poor, and it often flooded. But it enabled continued resistance and helped keep civilians alive. A section (100 m) of the tunnel has been preserved and turned into a museum.

Our next stop was Hotel Osmica.

Before the Bosnian War, Hotel Osmica was a regular hotel and scenic restaurant, located on the slopes of Mount Trebević, overlooking Sarajevo.

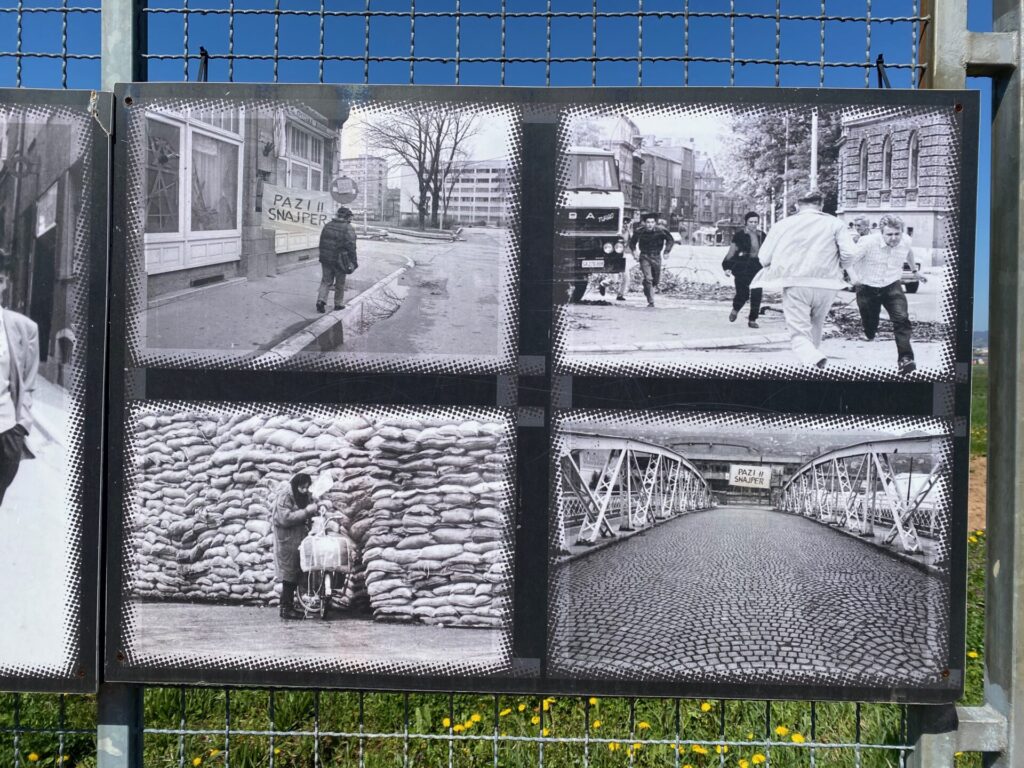

Once the war started, Osmica was seized and used by Bosnian Serb forces. Because of its elevated position, it offered a clear line of sight over Sarajevo. This made it a strategic military point. Osmica became a well-known sniper and artillery position from which Serb forces shelled and shot at the city below. Civilians were the primary victims. Snipers and spotters operating from Osmica were responsible for the infamous “Sniper Alley” phenomenon, where even the simplest walk across a street could become deadly.

The site was fiercely contested and changed hands several times.

Olympic Bobsleigh and Luge Track

The bobsleigh and luge track on Mount Trebević was built for the 1984 Winter Olympics. During the siege, Bosnian Serb forces used it as an artillery position and defensive trench. The curves and concrete walls provided excellent cover. After the war, the track was left in ruins, covered in graffiti and shrapnel scars. Today, it is used recreationally by bikers.

Old Jewish Cemetery

The Old Jewish Cemetery in Sarajevo is one of the largest and oldest Sephardic Jewish cemeteries in Europe. It is located on a hill overlooking the city. Early in the siege, Bosnian Serb forces took control of the cemetery and used it as an artillery and sniper position. From there, they had a direct line of sight over much of the city, targeting civilians and defenders. The cemetery was badly damaged from fighting, but it has been partly restored. Many gravestones still have bullet holes.